Ambition vs Action: New York’s Climate Leadership Gap

In 2019, New York passed one of the most ambitious climate laws in the nation, the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act (CLCPA). Six years later, apart from some impressive progress in solar and battery storage buildout, renewables penetration has fallen short of expectations, fossil fuel use is barely down, and frontline communities exposed to the worst air pollution are still waiting for relief. Furthermore, Trump is just 100 days into his second term, and the Administration has already sought to handcuff state-level climate action, targeting New York and its Climate Superfund Act while also halting a major offshore wind project and attempting to kill congestion pricing in NYC.

So, now more than ever, climate leadership will be largely left to states, cities, the private sector, NGOs, and philanthropists – and there are few states as well-positioned as New York to make progress. Yet, the frustrating factor is that the limited climate and clean energy progress to date has not been due to a lack of laws or ambitions. Instead, it’s the result of political gridlock in Albany even during a period when Democrats have held a supermajority. A wide rift exists within the environmental community that has stymied progress, especially with respect to matters beyond solar and battery storage; e.g. transportation, heavy industry, agriculture, etc. The State’s unique carbon accounting system is a real hindrance to progress and funding is increasingly a challenge. There is cause for hope in that proven strategies to help achieve the state’s goals are available, but first let’s look at the mandated targets set forth under the CLCPA.

CLCPA: An Ambitious Initiative Aimed at Economy-Wide Decarbonization

The passage of the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act created a wave of excitement within progressive circles by laying the foundation for a complete, economy-wide shift away from fossil fuels. Key provisions/targets mandated by the law include:

● 40% GHG emissions reduction by 2030 (from the 1990 baseline) and 85% by 2050

● 70% zero-emission electricity by 2030 and 100% by 2040

● 100% light-duty zero emission vehicle (ZEV) sales by 2035, transitioning non-road and medium/heavy-duty vehicles to ZEVs by 2035 and 2040, respectively, and enhancing public transportation

● Prioritization of disadvantaged communities, by directing 35% of funding toward projects that would address longstanding inequalities

At the outset, the Law also required the creation of a Climate Action Council that would oversee the development of a Scoping Plan through a 3-year public process, which wrapped up in early 2023. According to the State:

“This Scoping Plan includes recommendations to meet the Climate Act’s nation-leading goals and requirements… which will put New York on a path toward carbon neutrality while ensuring equity, system reliability, and a just transition from a fossil fuel economy to a robust clean energy economy….

This Scoping Plan provides recommendations for both sector-specific and economywide actions to achieve the Climate Act’s goals…it is fundamentally driven by the need to deliver on climate mitigation, justice, economic opportunity, and long-term job opportunities for New Yorkers.”

For additional details on this process or the final Plan, you can read more HERE.

Where We Are Now: Gauging Progress Six Years Later

Only Minor Overall Reductions in NYS Greenhouse Gas Emissions, and Increasing Since the Pandemic

As you can see in the chart below, New York’s overall greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in 2022 were 9.3% lower than the 1990 baseline. Progress has been minimal since around 2010, and the only major dip was during the Covid pandemic. GHG emissions increased in 2021 and 2022 as the economy recovered, although they were slightly lower than in 2019; this does not bode well for reaching the mandated 40% reduction by 2030 (shown by the larger green bar on the right of the chart).

Most of the GHG reductions made in NYS involved CO2 (shown in blue on the chart) being trimmed from industry, transportation, and electricity generation. Methane (the grey bars) has barely dropped at all, and agricultural emissions of methane actually rose substantially.

Energy Vision concluded in its November 2023 report, Putting New York’s Organic Waste to Work, that reducing methane is essential for New York to meet its 2030 climate goal, because CO2 can only be cut so far in the next few years, and the going is getting tougher as plans for mass electrification stall. Plus, as the chart also shows, even if NYS could magically eliminate all CO2 emissions overnight, that wouldn’t be enough to reach the 2030 goal, since that green bar is larger than the blue component. And no one realistically thinks NYS could cut all or anywhere near all its CO2 emissions in the next five years.

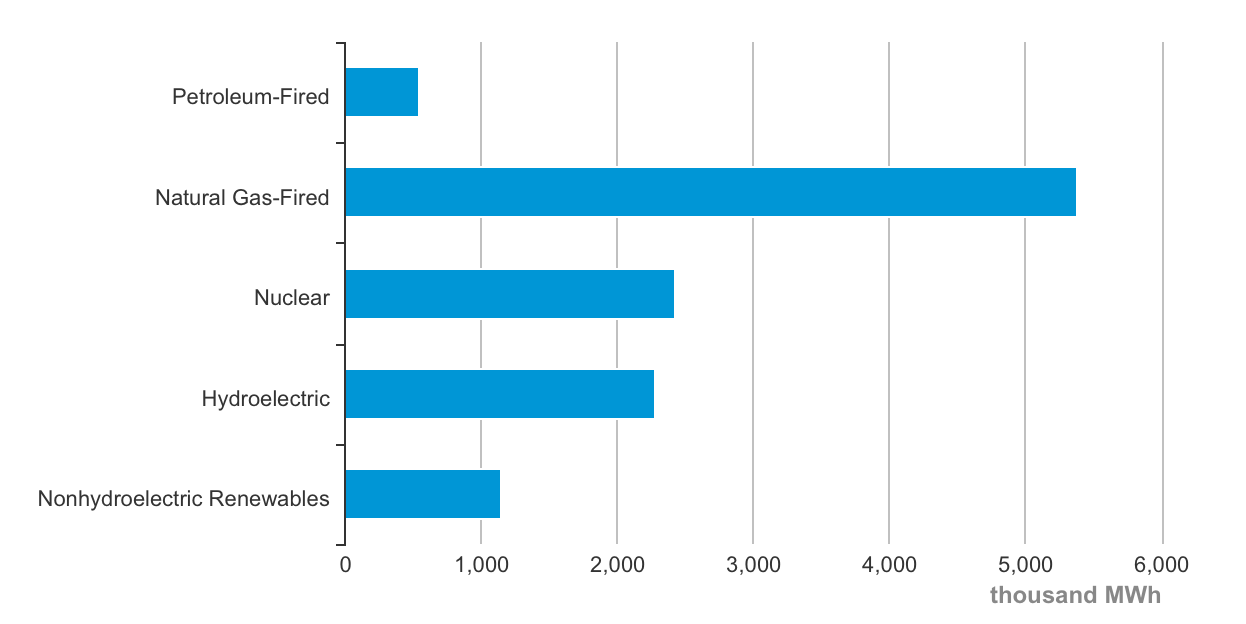

The Electric Grid is Still Heavily Reliant on Fossil Gas

The EIA graph below shows that NYS currently generates a bit over half of its electricity from fossil fuels (almost all of which is natural gas), and just under half from nuclear and renewables. It would be virtually impossible to replace 20 percentage points of electricity generation from natural gas with renewables in the next five years, especially in light of delays in offshore wind, solar and transmission projects.

New York State Net Electricity Generation by Source, Jan. 2025

New York had staked its hopes for decarbonizing the electric grid on massive offshore wind projects to provide power for the downstate region (including New York City and Long Island) in particular. Yet project developers have pulled out amid rising costs, and there is now active hostility and permit revocations from the Trump administration.

Meanwhile, buildings have been slow to adopt electrification in NYS given the high costs. Installing heat pumps in new buildings is one thing, but retrofitting existing gas-fired buildings, especially large older ones in New York City, is often prohibitively expensive.

Mixed Results in the Transportation Sector

The numbers of electric vehicles (EVs) deployed in New York State are increasing in the passenger car and light-duty truck categories, where they work well and where they can feasibly charge their batteries.

But in the heavy-duty truck sector, EVs are not a commercial choice for most fleets today. They typically cost 2-3 times the price of diesel trucks. They don’t perform reliably. Their heavy batteries mean reduced payloads, and their extra weight puts added strain on roads. Beyond all this, there is a near-total lack of high-capacity commercial charging stations in key trucking corridors in NY. In fact, New York’s recent widespread remodeling of Thruway plazas did not put in a single commercial electric charger for trucks, only small-capacity chargers for electric cars.

So, overall, there are major implementation and funding lags in reaching New York’s steppingstone climate goals for 2030, let alone the hugely ambitious ones for 2040 and 2050.

“Big Talk and Limited Action” – Identifying Obstacles Impeding Progress

While we won’t attempt to cover all the reasons for the gap between New York’s goals and its only modest progress to date, there are certain fundamental challenges that deserve discussion, especially as they relate to the biofuels arena. They include:

The CLCPA’s Unique Carbon Accounting System is Problematic

From the outset, the CLCPA set up an unusual carbon emissions accounting system for New York State. Unlike the federal government, California, and other states with progressive climate programs, it does not consistently tally the “full carbon footprint” of all of its energy sources – e.g. the “upstream” emissions coming from production of its energy sources (wherever they may be) as well as the “direct” emissions generated by the energy or fuel when it is used in New York.

For example, the CLCPA accounts for upstream emissions from out-of-state oil and gas production, i.e. these emissions are now counted toward New York’s GHG inventory. But it does not take into account any upstream avoided emissions from biofuel production, whether in-state or out of state. And this is not a trivial issue; almost 12% of New York State’s methane emissions come from oil- and gas-related infrastructure, while nearly three times as much – 34% – comes from waste and manure, which are feedstocks for making domestic, low-carbon, renewable biofuels.

So, consider this: the GHG emissions from fossil gas and renewable natural gas (RNG, which is derived from decomposing organic waste streams rather than extracted from deep underground) used in New York are deemed equally harmful under state law. This is despite the fact that, on a lifecycle basis, production of fossil gas causes significant amounts of methane to leak from drilling operations, while production of renewable natural gas actually captures methane from waste that would otherwise be emitted into the air.

In fact, RNG made from organic waste can be better than net zero; it can be net carbon negative. When made from food scraps or manure, RNG production captures more GHGs (in the form of very potent methane) than are released when it is combusted (as less potent CO2). To count upstream emissions of methane toward New York’s GHG inventory while simultaneously excluding avoided upstream emissions from biofuels is not a fair and accurate representation of reality, nor is it based on the best available science and data.

The CLCPA Uses a 20-year Rather than a 100-year Global Warming Potential (GWP)

Most of the world uses a 100-year GWP to measure the impacts of different greenhouse gases, but New York’s use of the 20-year GWP better accounts for the frontloaded impact of methane. This increases the emphasis on reducing methane emissions, in line with the international scientific community concluding in 2021 that global methane emissions needed to be cut at least 30% by 2030 to avoid runaway climate change. Yet by combining a 20-year GWP with a carbon accounting methodology that ignores upstream avoided emissions (primarily methane), New York’s system is cherry-picked to paint ALL natural gas (fossil or renewable) in the same light: as being very bad for the climate and therefore a primary target for replacement.

The CLCPA’s Stated Purpose is Net Zero Emissions by 2050 but Details Are Unclear/Contradictory

Beyond its questionable carbon accounting, the CLCPA’s stated purpose is to achieve net zero emissions in all sectors of the economy by 2050. However, other provisions of the law are ambiguous or contradictory about what qualifies as “zero emissions” versus “net zero emissions.” Depending on interpretation, RNG could either be excluded from the options for having some tailpipe CO2 emissions when combusted or included for having net negative lifecycle GHG emissions when factoring in all the avoided methane from its production.

The NYS Public Service Commission has taken this matter up (public comments were due in January), but final guidance is pending. It’s fine and often fair to dislike combustion (of anything, anywhere), but if New York is serious about limiting its available options for economy-wide decarbonization to solar, wind, fuel cells, heat pumps and batteries, achieving many of the goals set forth under the CLCPA will be extremely challenging, if not impossible.

New York’s Political Will Has Not Been Matched by Political Action

Strong rhetoric from New York lawmakers has rung hollow in the face of weak follow-through. In part this is due to private sector resistance to CLCPA implementation, including pushback and lobbying from utilities, real estate firms, and fossil fuel interests. There are also convenient economic excuses for inaction, including inflation, supply chain issues, and the lingering effects (real or imagined) of the pandemic.

But the crux of the matter is that New York lawmakers have not yet provided feasible pathways to meet the lofty goals of the CLCPA. Without the tools necessary to get the job done (see next section), these targets will remain far out of reach. There is a Democratic supermajority in the state legislature, so in theory this problem is solvable, but there are growing internal rifts over implementing the CLCPA (and other climate laws like the Advanced Clean Trucks rule copied from California without the same degree of infrastructure support).

Many environmental organizations have argued that the goal in New York State is to “electrify everything,” despite the fact that several high-impact sectors cannot find affordable or technologically viable solutions in this area: heavy-duty transportation (including trucks, trains, planes, and ships), old buildings, and heavy industry. Furthermore, this one-size-fits-all prescription is now on shakier ground amid spiking electricity demand from AI data centers and rising costs for ratepayers.

Much of the support for the CLCPA’s passage in 2019 came from assurances that the state’s massive energy overhaul would be affordable and wouldn’t leave disadvantaged communities behind. The cost factor alone seems to be eroding support when there are cost-effective solutions available now in addition to electricity. So, what is needed is a broader suite of eligible low-carbon solutions, not an ideologically rigid focus on electricity generated from solar, wind, and hydropower alone. As 2030 draws nearer, there is active legislative debate about whether some CLCPA provisions and/or the timelines should be altered to reflect market realities and feasible paths forward.

There Are Many Regulatory Bottlenecks

As in the rest of the country, delays in permitting and transmission infrastructure due to regulatory bottlenecks are a big issue in New York State. For example, a report issued last year by the Office of the New York State Comptroller looked at 15 large-scale renewable energy projects in NYS that applied for siting permits from 2020-2023. It found that the average time for one to be granted was nearly 3.7 years. That’s just for one permit out of many ultimately required per project. Reforms are sorely needed to expedite the permitting process. And now, with the federal government actively trying to block NYS clean energy projects by revoking permits within federal jurisdiction (the offshore wind project mentioned previously), the matter has only worsened.

For New York State, Prioritizing Proven Approaches is Critical

New York has ambitions to be a global leader in accelerating the energy transition, but the pace of progress has been far slower than projected, and headwinds are mounting. While it’s great to set ambitious goals, if they are not technologically, economically, or politically viable as first envisioned, leaders need to reassess and adapt accordingly. And with the unprecedented rollback in federal support and leadership on climate, clean energy, equity and a growing list of other policy priorities, states are critical actors in maintaining momentum and progress, along with cities, the private sector, and philanthropies.

Based on Energy Vision’s independent research, there are a number of exciting opportunities to accelerate the energy transition within the broad framework set forth under the CLCPA. Here are two significant steps the State can take now:

1. Adopt a “Full Lifecycle” Carbon Accounting System

This means properly measuring and characterizing the role of each fuel, including any avoided upstream emissions.

It is hard to argue that New York’s current carbon accounting methodology is objective, fair, or an accurate representation of climate impacts when various aspects of the current methodology cherry-pick data to align with an “electrify everything” agenda. (As mentioned earlier, upstream methane emissions from out-of-state fossil natural gas consumed in NY are counted; whereas avoided upstream emissions from biofuels are not.) Ultimately, the environment doesn’t care if methane emissions are generated upstream or downstream. Wherever they come from, they have the same damaging impacts. As such, we should prioritize reductions in methane emissions across the board, regardless of where they come from, and account for them in a way that rewards methane-cutting activities.

In evaluating each energy source, particularly in the transportation sector, the gold standard is the Greenhouse Gases, Regulated Emissions, and Energy Use in Transportation (GREET) model, developed by the Department of Energy’s Argonne National Lab. This model is rooted in sound science and its derivative, developed by California’s Air Resources Board – CA GREET – is linked to billions of dollars in infrastructure investments made over the past decade plus.

Net zero emissions fuels – using consistent lifecycle carbon accounting methodologies – should qualify for favorable treatment under the CLCPA, in alignment with the stated purpose of the law.

2. Adopt a “Clean Fuel Standard” (CFS) for the Transportation Sector

Such standards have been adopted by California (the first state to implement one, in 2011), Oregon, and Washington State, and New Mexico passed legislation to do so in 2024. Each state measures the carbon intensity of every fuel used in its transportation sector on a lifecycle basis. The state then sets targets for decreasing the sector’s overall carbon intensity. Producers of high-carbon fuels must reduce their carbon intensity or buy credits generated by producers of low-carbon fuels. And as the targets get tighter each year, they drive production of the lowest lifecycle GHG-emitting fuels that earn the most credits, like RNG and electricity from renewables.

The positive climate and clean fuel impacts from California’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard speak for themselves. As detailed in a recent Energy Vision post, over 31 billion gallons of petroleum fuels have been displaced since California’s program began in 2011 and progress has been years ahead of schedule. By 2023, the state had cut the carbon intensity of its transportation sector by more than 15%, reaching that target three years early. The latest revisions (which should be finalized shortly) deepen the program’s targets to a 30% reduction by 2030 and 90% by 2045. For another great summary of how these programs work, check out this piece from Rocky Mountain Institute in March.

Right now, proposals for Clean Fuel Standards are pending in 11 states, including New York. A CFS would greatly incentivize increased production and use of renewable diesel (RD), renewable natural gas (RNG), battery-electric vehicles (BEV), and hydrogen fuel cell vehicles. Since high-carbon fuel producers would be paying for low-carbon fuel companies to expand their output, the policy would come at minimal taxpayer expense. This is a crucial consideration for strained state budgets – especially amidst looming cuts and uncertainty in federal funding for various state programs on transportation and the environment. A CFS would also generate funds for electric chargers and public transportation. Energy Vision laid out this whole case in a May 2nd op-ed in City Limits, calling for the NYS Legislature to pass a Clean Fuel Standard this year, not punt it to next year.

Less Talk, More Action

In New York, Governor Kathy Hochul just proposed a budget that includes $1 billion in climate funding, with details forthcoming. This is a welcome development, but by itself it isn’t going to move the needle much, nor is it going to be nearly enough to accelerate the pace of economy-wide change envisioned by the CLCPA. It also doesn’t do much to address the underlying obstacles hindering more rapid action.

While it’s great for New York to be a testbed for innovative climate policy and programs, we don’t have the luxury of time, and we’re facing an increasingly challenging environment for clean energy. It’s long past time for the Empire State to move more rapidly.

Passing a Clean Fuel Standard this year would especially signal that New York is finally ready to get down to business. Fixing the flawed carbon accounting system and prioritizing a more comprehensive suite of solutions to enable true economy-wide decarbonization would help a lot as well. It’s not too late for New York to lead, but to continue down the same path with the same constraints and expect different results is wishful thinking.